“I don’t want to stay here because they’re horrible people. They’re horrible to us. They try to make our lives difficult – as if it’s not difficult enough. You English, you’re so kind. Are all people like that in England?”

Such was the recurring message that confronted Paula Erol at the makeshift refugee camp known as The Jungle, outside Calais, earlier this month (November).

She described a camp increasingly cut off from the outside world and patrolled by riot police “dressed like Transformers”. They block access and mount dispersal operations with the apparent intention of reducing its 6,000-strong population by two thirds.

The refugees’ view of the UK couldn’t contrast more starkly. While the French police fire stun grenades, rubber bullets and water canon to contain them, what relatively little comfort they do enjoy is largely thanks to British donors.

“That’s the impression they get,” said Paula. “Someone said to me: ‘Loads of English people come over to help us and they’re really kind.’ I didn’t want to burst his bubble. ‘The people are, yes,’ I said. ‘But the politics, no.’”

Paula, from Broadstairs, was one of a collection of Thanet people who have launched appeals for food, clothing, sleeping bags, shoes and other goods over the last few months and crossed the Channel to distribute them among The Jungle’s inhabitants.

She was joined on the trip earlier this month (November) by fellow Broadstairs residents Joyce Edling and Aram Rawf, who himself escaped war-torn Iraq with thousands of other Kurdish refugees.

What they saw was a mass of people from a variety of unstable and/or impoverished, mainly African and Middle Eastern nations who now face increasing political hostility, in addition to institutional isolation, in France.

Their actions belie the fact that just a few short months ago, Thanet looked likely to become Nigel Farage’s political bridgehead for UKIP’s anti-immigration, anti-EU message.

In a journal about her visit, Joyce wrote: “The Jungle is exactly how I imagined it would be: mainly scruffy tents and tarpaulins inhabited by desperate people, trying to make the best of their situation. The rain did nothing to enhance the appearance. Indeed, we were walking ankle-deep through mud.”

Last Friday’s ISIS attack on Paris has darkened the political climate further, raising the likelihood of a backlash against the refugees, even though it was such cold-blooded brutality that drove many of them to Calais in the first place.

“It’s moving how they get on and have a life,” Paula said. “People sitting around cooking together, making coffee together, children playing. Obviously, they’re not happy there but what choice do they have?

“The general atmosphere on the camp is stoic and friendly. I said ‘morning’ to everybody I passed, whether they looked or smiled at me or not, and I always got a good response. People always responded with a smile.”

Until recently, it was possible to rock up in a van to help out and deliver donations directly to The Jungle. However, in recent months, the French authorities have restricted access to only volunteers issued with passes, and even this limited contact with the outside world is under threat.

So now, the constant stream of donations are delivered to ‘The Warehouse’, a short distance away. Its location is not widely publicised to avoid far-right groups from targeting it – both the English Defence League and Pegida have been active in Calais.

With the exception of Médecins Sans Frontières and Doctors of the World, there are no recognised non-governmental organisations (NGOs) managing the site. Instead, Paula, Joyce and Rawf arranged access with a non-profit solidarity organisation working on the ground. They were emailed details of where and when to turn up, as well as the times of the briefings at which volunteers can choose which of the day’s projects to be involved in.

But despite the lack of NGOs, what system there is seems to function well.

Aram speaks Kurdish, Arabic and Farsi, and spent his time working as an interpreter. He was so busy that, once there, his compatriots barely saw him during their stay. Meanwhile, Paula and Joyce spent their first day helping to sort donations in The Warehouse, before they participated in cleaning and other projects on the camp itself.

“We unpacked the car and shared a cup of coffee with some friendly helpers,” wrote Joyce in a journal about her experiences there. “About 20 volunteers were sorting through a colossal mountain of clothes in cartons and bin-liners. The task looked unsurmountable.

“The variety of articles was astonishing. How could people imagine that DVDs, stiletto heels and electric toothbrushes could be useful for refugees living at best in tents and at worst in the open air?

“Having said that, there was a simply amazing amount of fantastic clothing, a lot of which seemed quite new or hardly ever worn.”

The following day, Joyce and Paula reported to The Warehouse for the 9am briefing. “We stood round in a circle [for] a sort of yoga session to loosen us up,” wrote Joyce. “We are really impressed by the organisation here. No one seems to be in charge and there is no real rota as such, but somehow it all works.”

They joined around 40 volunteers for yet more sorting, among them Jeff, who had travelled to Calais all the way from San Francisco. Then it was off to help the various communities clean their area of the camp, and leave gloves, bin bags, sanitation gel and litter pickers so they can manage it themselves.

“This was our first introduction to the camp’s inhabitants,” wrote Joyce. “At one point, I heard a shout ‘Hellooooo!’ I turned round and there was such a sweet little Kurdish girl, about four years old, who then launched into helping us with great gusto. Another girl about the same age joined in. The innocence of children! They thought it was a fun game.”

Joyce said she found the work “back-breaking, even though it doesn’t involve any hard labour at all”. And Paula definitely agreed: “We were so busy that we were totally and utterly knackered by the end of each day.”

Shoes are in great demand on the camp. Many of The Jungle’s inhabitants struggle around in flip-flops or walk the unforgiving, muddy terrain with their heels sticking out of shoes that are far too small.

Said Paula: “On the Friday morning, we sorted in The Warehouse before doing the clean-up. We were advised to take a shopping list if we saw anything that people needed, and to liaise with the communities to see if there was anything they wanted us to bring back.

“We came back with a shopping list of mainly shoes – they’re desperately in need of shoes. The next day, we sorted for another hour or two and made up our shopping list and went back to give them out. We went to visit the women’s centre, because we had a big box of Lego to donate, but Saturday was ‘beauty day’. I’m a masseur, so I got nabbed and spent the rest of the day giving massages to about 14 women. That was exhausting.

“On the Sunday, we took as many shoes as we could carry into the camp, but they were quickly gone. We were surrounded by people needing shoes. We wrote down people’s names and their shoe sizes and went back to The Warehouse, did some sorting and arranged to give them out at the water tap [on the camp].

“But, of course, people saw us carrying the bags through the camp, so they followed us. When we reached the tap, not everyone had turned up, so there were maybe eight pairs of shoes left. Lots of the people who had followed us wanted shoes, but how do you decide who gets a pair?

“You look around at this sea of faces and say ‘what size are you?’ They say ‘42’ and, as you get them out, there’s eight hands all trying to grab them.

“At one point, two guys grabbed one pair tied together with their laces and they were struggling. One of them was really angry.

“At the end of it, there were plenty of people who didn’t get. At one point I said: ‘Guys, guys, if it was possible, I’d open a shoe shop for you all.’ That kind of diffused the atmosphere. Some people laughed and tempers calmed, and some people came up and said ‘you’re really kind, thank you very much’.

“It was horrible to see people reduced to scuffling over something as simple as a pair of shoes.”

Both Paula and Joyce stress that the shoe incident was rather out of keeping with the rest of their time there, during which the desire for basic human dignity was clearly in evidence.

Said Paula: “As we were coming away from the shoe debacle, a couple of guys approached Joyce and said ‘I’ve got a €500 note, can you change it for me?’ She tried to give him a €250 note, but he just refused it. He was adamant he didn’t want it. He kept saying: ‘My friend, I just want change, please.’

“I’m sure a lot of British people think they’re criminals and crooks that would stab you in the back as soon as look at you, but even when someone tried to give him €250, he did not accept it.

“There might have been some cultural thing about taking money from a woman, but I think that was just stunningly admirable. He might not have been poor – after all, many of them have sold businesses and houses, and have left good jobs, cars and the rest of it.”

As if to emphasise the point, Paula and Joyce met Abdul Rahman, a linguist and university professor in his previous, more settled life. He helped them carry the bags of shoes, and insisted on being called by his first and last name.

“That really impressed me because, in the midst of all this crap, his loss of status – his loss of everything – he was holding onto his dignity,” said Paula.

“When Joyce and I were leaving the camp, he caught up with us again and thanked us for the shoes and for doing the distribution. I said to him: ‘Do you try to get on the lorries, Abdul Rahman?’ He said yes. And, I asked, if you get to Dover, what next? He said: ‘I don’t know.’”

The UK’s tightening border controls and the calls for reprisals against ISIS from the West makes this a particularly testing time for the refugees. Trying to maintain any hope of finding a better life – currently defined as getting inside or clinging to lorries and trains long enough to cross the Channel – is proving difficult.

The French police are becoming ever more punitive, not only when they catch a refugee near the ferry port or the Channel Tunnel, but also in The Jungle itself.

Joyce described how the police caught a teenage boy near the tunnel. They confiscated his shoes, so he had to walk bare-footed back to the camp. Next time, the officers told him, they would also take his trousers.

Encouraged by the sense that Britons are a generous breed, the bulk of the refugees still doggedly cling to the hope for a lucky break – if only because there appears to be no alternative.

Said Paula: “They’re very aware that it’s getting harder to get into the UK. Some Sudanese guys we met were upbeat, but they were saying ‘yes, I want to get to the UK, but I don’t think it’s going to happen’.”

Joyce also wrote: “I never cease to be astonished at the strength of the human spirit. So many people I met are doing so much to make the most of their miserable existence in the squalor. It is moving beyond belief.

“Along with this experience is my pride at all the help and support that so many from the UK are giving – from ordinary people to churches, schools, ex-army officers and charity organisations. The enormous mountains of clothes and food, the many vans which turn up loaded every day from all parts of the UK, the commitment of so many wonderful volunteers. It made me (uncharacteristically) proud to be British.

“One of the few French people there said he was ashamed at the paucity of helpers and donations from France. No wonder the refugees tell me – often with tears in their eyes – that they love the English.”

- This article first appeared on Thanet Watch on November 19, 2015.

Current priorities

List created and updated weekly by L’Auberge + Help Calais

- Pre-made identical food parcels. For further information, please see this list.

- Volunteers – especially if you can stay longer than a day or two. Please complete the form for new volunteers or returning volunteers.

- Blankets

- Warm, four seasons sleeping bags

- Tents (preferably four-man or larger)

- Sleeping mats

- Firewood

- Fire extinguishers (smaller, kitchen size – powder or foam)

- Wind up or solar torches and lanterns – nothing that requires an electricity supply or batteries

- Men’s waterproof walking boots with high ankle and trainers – especially sizes 42 and 43

- Women’s boots or shoes up to size 39. No heels

- Warm, waterproof winter jackets

- Socks

- Underwear – men’s, women’s and children’s

- Goody bags of hats, gloves and scarves

- Men’s jogging bottoms or jeans, especially black, from sizes 28 to 36

- Flat pack cardboard boxes (size 60x40x32.5 or 90x60x48)

- Builders

- Building materials, including wood, nails, rope and tools

If you are taking any building materials or have building skills you’d like to put to good use, please email: calaisbuild@gmail.com.

How to organise donated goods

Try to concentrate on one or two items as a large amount of one item is much quicker and easier to distribute than a mixed load of many items.

It is very important that goods are clean, pre-sorted and clearly labelled – for instance, a box of walking boots size 44, a bag of men’s jeans size 32 or pre-packaged food parcels.

If you want to be a real star, then the best box sizes are 60x40x32.5 or 90x60x48

How to donate

To deliver aid to The Warehouse and/or to arrange distribution in the camp with the support of experienced volunteers, please complete this form.

If you have any questions, please email them to calaisdonations@gmail.com.

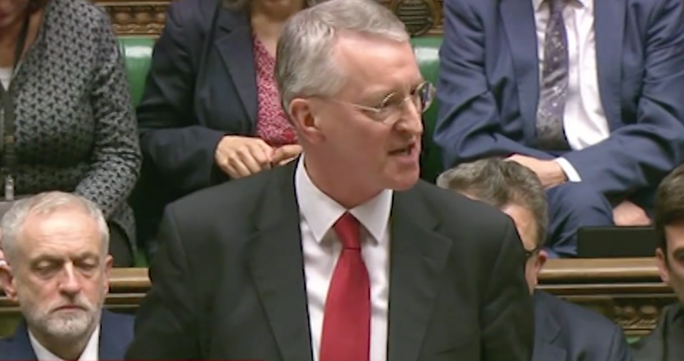

Picture: Refugees with placards stating their name and where they want to end up. That was used by CalAid, the non-profit organisation.